In a war that was so destructive, so much was created…

In a war that was so destructive, so much was created…

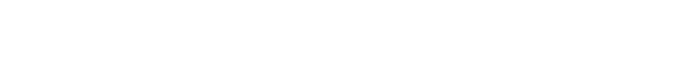

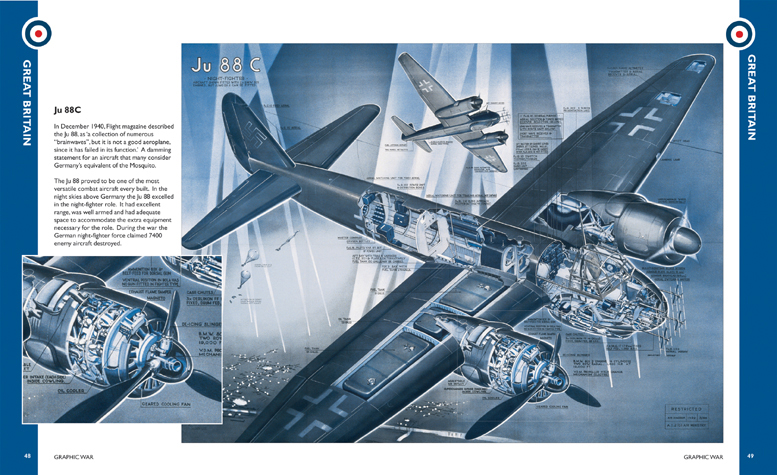

The idea for Graphic War came about when I was writing and assembling my second book, Gunner. An Illustrated History of World War II Aircraft Turrets and Gun Positions. While doing research at the RAF Museum, I came across a number of “air diagrams.” These were large, poster-sized cutaway drawings of British aircraft turrets. I also discovered a wonderful cutaway of the Junkers Ju 88, drawn by Kerry Lee. The drawings were infinitely fascinating and each illustration a piece of art in itself. While most of the drawings were of machines and equipment, many had an abstract, aesthetic quality to them. So began the idea for this book.

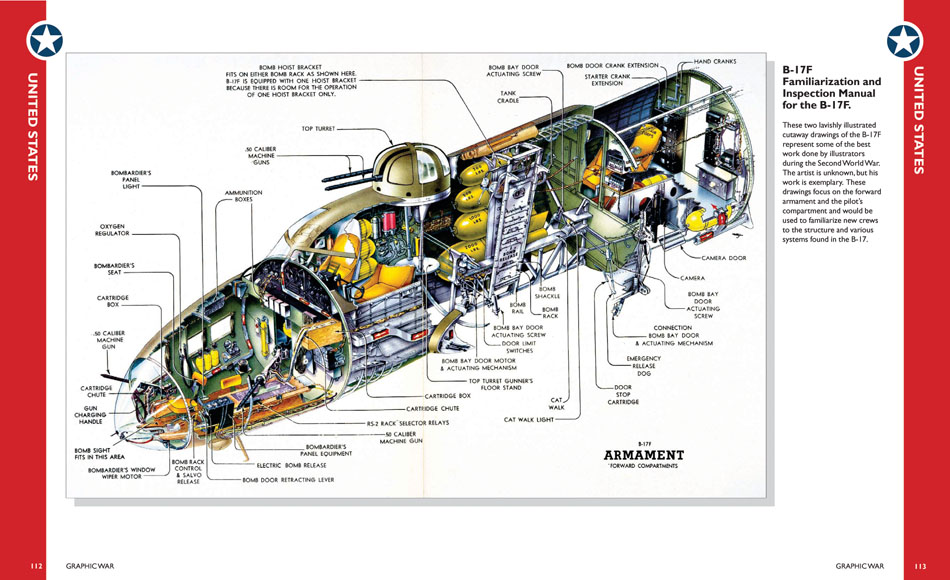

World War II was a highly mechanized war. In a very short period of time, the aircraft of World War I gave way to the stressed-skinned all-metal monoplane fighter and bomber. These complex aircraft required a new level of skill to fly and a whole new training regimen. Aircrew and ground crews now had to deal with greater speeds, higher altitudes, accurate navigation, sophisticated hydraulics, radar, superchargers and more powerful engines. Applicants of the highest degree were recruited for training, and training methods had to be developed to ensure the best and quickest techniques were used to meld these trainees into aircrew of the highest quality.

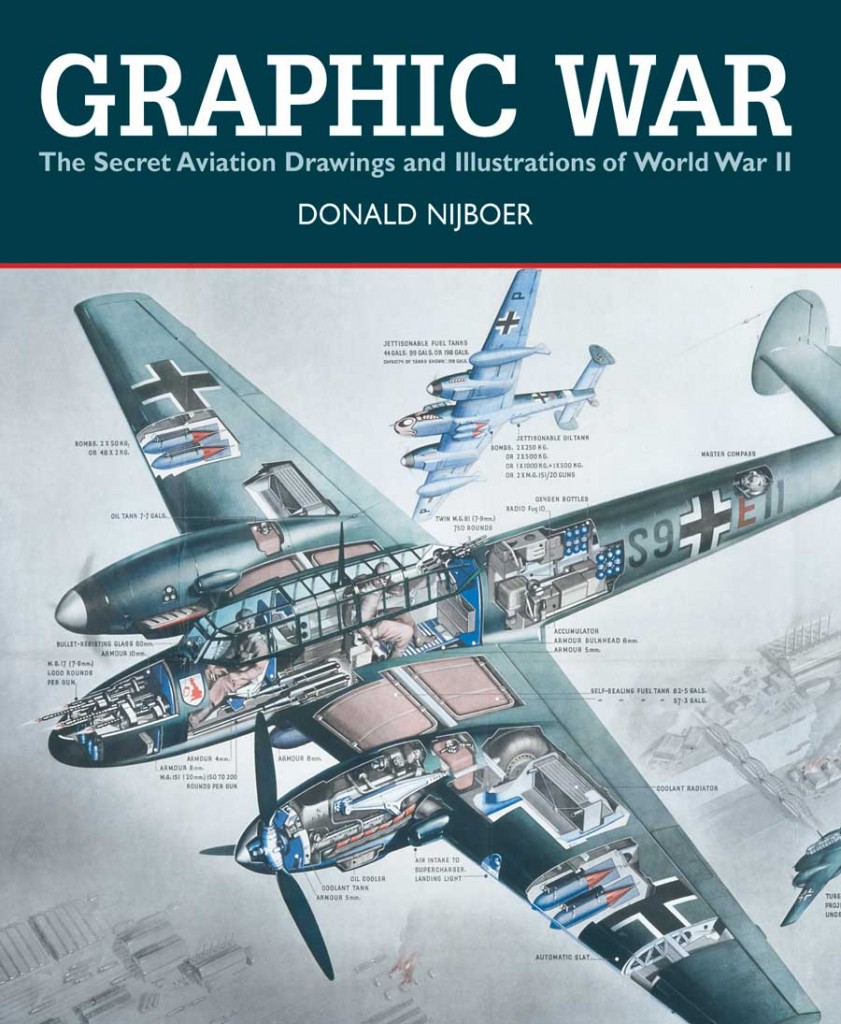

A big part of the training of aircrew involved the use of visual aids, in poster form and in illustrations found in manuals. Many of these drawings were three-dimensional perspective drawings. Unlike traditional two-dimensional engineers’ drawings, these were designed to be easily deciphered by the thousands of new recruits.

In Britain, the source for this material was the Air Ministry and the Ministry for Aircraft Production. During the war, thousands of air diagram posters were produced. These 40-by-30-inch works of art are the most impressive pieces in this book. They include everything from multicolored cutaway drawings of enemy aircraft to simple illustrations bearing reminders such as “Beware of the Hun in the Sun.” All this material was “Restricted — Official Use Only,” and most of it has never been published before. In the United States, a wealth of graphic illustrations and cutaway drawings can be found in the thousands of manuals published during the war.

The U.S. Air Training Division also created posters, but very few of these have survived. The Axis forces were similarly very busy producing illustrations for their manuals and posters. However, where Allied manuals were lavishly illustrated (with, for instance, the addition of cartoon characters and pen-and-ink drawings of aircraft flying through the copy), German manuals were well illustrated but without the frills. Their posters, however, were just as detailed and as well crafted as those of their Allied counterparts. Many military documents were destroyed just before and after the end of the war, and so illustrations from Germany, China, Russia and Japan in particular are very hard to come by and the examples in this book are rare survivors of that time.

The illustrations included in the Image Collections section of this book are organized by country of origin — Great Britain, Germany, the United States and the Soviet Union. So, for example, you can compare the British renderings of a Junkers Ju 88 (at pages 54-5 and 64-5) with the German drawings of the same aircraft (starting at page 180). Out of all the artists, illustrators and technical artists employed by the Allies and the other major combatants, most remain anonymous. Almost all of the drawings still in existence are unsigned and uncredited, no doubt primarily because of the top secret nature of the work. Some of the artists had jobs in commercial art and design before the conflict began and found other, similar employment once the war was over; others continued to work as technical artists for aircraft companies in the postwar years.

The featured artist for this book is Peter Endsleigh Castle. I had the pleasure of interviewing him in the fall of 2003. His first-hand account of what it was like to work for British Intelligence and the part he played creating illustrations while working for the RAF’s 1426 Flight, the Enemy Aircraft Evaluation Unit, is fascinating. His amazing drawings are among the hundreds that can be found this book.

The artwork in this volume is not meant to be viewed as a celebration of war. While today we can calmly view the images and read the instructions on how to abandon a ditched aircraft, we can only imagine what it must have been like to be twenty years old, flying in a stricken aircraft about to crash-land in complete darkness on the surface of the North Sea or Pacific Ocean. The illustrations in this book give us a brief insight into the world of the air and ground crew trainee. All that we see, they had to learn, absorb and memorize. It was an enormous task and one that would have not been possible if not for the talent and creativity of the artists employed.

While most governments employed war artists to record the battles and to further propaganda efforts, the artwork in this book was created for a very different purpose — to help young men win the battles and, it was hoped, survive the war.

By Donald NIjboer